Photograph depicts Mary John shaking hands with unidentified man at official ceremony where she was awarded the Order of Canada for outstanding service to her community. Two unidentified woman stand in background in large ornately furnished room.

Audio recording consists of an interview conducted by Bridget Moran with Mary John.

Audiocassette Summary

00’05” Bridget is interviewing Mary John who discusses a potlatch held at Stoney Creek that Bridget attended. Bridget asks about the talking stick and she asks Mary John to explain its significance. Mary explains there had been a naming ceremony about a year ago and that a woman named Maisie had changed clans from her mother to her father’s clan. Mary notes while this is unusual, her father’s only son had died and therefore requested that the daughter changed clans. At this ‘September potlatch’ therefore this woman had to change tables at the potlatch.

04’00” Mary explains the context of the September Potlatch. She notes that Maisie had hosted this potlatch to pay back for the gifts that had been provided for her from a year ago when she received a new name. They then discuss the amount of money that the host gave to the guests and the amount of money that is normally provided – there is no particular amount ‘whatever you wish’ Mary notes she had provided Maisie with a gift last year of $100 but that Maisie gave her back $200 – that is not required – there is no required amount

07’30” Mary explains that at a potlatch you are expected to bring a case or few bags of food

08’00” Mary discusses the type of food provided at a potlatch; it is traditional food not western food; Bridget notes there was caribou provided there. Mary explains that the host of a potlatch asks people to hunt for moose and deer meat in order to prepare for the food to be served. Bridget then talks about the food that was served and Mary notes it included also fish and beaver.

11’00” Bridget asks Mary to talk about the gifts given to her daughter Flo at the potlatch in exchange for a loan she provided to another woman whose husband had died a year before. Bridget notes it was a ‘touching’ moment.

12’00” Mary talks about the Priest ‘Father Brian’ who was at the potlatch. Four clans collected money and gave it to the priest for his work [missionary work?]

15’07” Mary explains the situation of Geraldine Thomas –that at the potlatch she was not seated before; that is she was not initiated before and so she was seated at the potlatch

15’57” Tape stops momentarily

16’09” Mary continues to talk about Geraldine and the potlatch events; the significance of the tapping of the talking stick; then she was seated and guests give her gifts. Then Mary talks about Ernie and her late daughter Helen who also wanted to cross their clan but that Mary ‘did not let her go’

20’00” Mary talks about the feelings of a child who gives up their clan and that it is like ‘giving up one of your children’ as Celina noted to Bridget at the event.

21’00” Mary talks about her son Ernie who crossed over to his father’s clan and that he was gifted at the potlatch

22’00” Bridget then notes that at this potlatch that the Frog Clan became host of the Grouse clan at this potlatch. Mary explains that the clan then had debts to pay at this potlatch.

26’00” Mary talks about the death of Stoney Creek members; she is unsure when there will be another potlatch in Stoney Creek.

28’00” Bridget notes that she did not understand the ceremony as it was in Carrier language; however Bridget notes it is a pity the white world doesn’t see potlatches as they are ‘so touching’

31’00” Mary explains that each clan takes care of the deceased family members and takes care of putting up the headstone

32’00” Tape ends abruptly

File consists of recorded audio interviews:

- Interview: Mary John, [Tape] 1 & 2, c.1986-1987

- Interview: Mary John, [Tape] 3 & 4, c.1986-1987

- Interview: Mary John, [Tape] 5 & 6, c.1986-1987

- Interview: Mary John, [Tape] 7 & 8, c.1986-1987

- Interview: Mary John 9 & 10 [#908 March 1985 CBC?], March 1985 [?] or c.1986-1987 [?]

- Interview: Mary John, August 1987

- Interview: Mary John - Cheslatta, 6 July 1993

- Interview: Mary John Potlatch, Terrace, B.C., 9 September 1991

File consists of a videocassette (VHS) recording of Mary John at Metlakatla in May 1994, originally filmed on a handheld camcorder on Video 8 cassette. Bridget noted in a later 1994 interview with Bob Harkins that this road trip was conducted for them to attend the basic education class at Metlakatla; this recording has also been reformatted on DVD.

Videocassette Summary

Context: Video-recording conducted by Bridget Moran with Mary John on their road trip to Metlakatla to visit the Elders Group there.

Highlights Include:

0’:05” Bridget Moran records on videotape Mary John in New Hazelton at the road side

1’00” Bridget Moran records on videotape Mary John in front of the totem poles in K’san ‘Old Hazelton’ and note they are heading by car to Prince Rupert

2’00”At Metlakatla Mary is shown eating fried dried seaweed in a hall in Metlakatla with a group of people

7’:35” Mary discusses working in the hospital and financially having a hard time as her husband was out of a job due to change in logging practices. He had a difficult time being at home and Mary sometimes had to walk to work to Vanderhoof, a distance 9+ miles from Stoney Creek. Talks about a time of having to walk to work on the ice and put bales of hay in her boots to walk on the ice

10’:35” Talks about the difficulties of working in the white world

11’:15” Talks about the time that her son made his First Communion; priest offered to buy lunch for all the children; Mary remembers having him ask if she and her son could come into the restaurant as normally they were not allowed to go to the restaurants

14’30” Sandra explains how they had decided to invite Mary to Metlakatla; she had read the Stoney Creek Woman book and wondered if Mary was still alive; she called the Band office in Vanderhoof and was connected with Mary’s niece who asks if she would come to Metlakatla. And then decided to invite Bridget as well.

18’37” Mary talks about the origin of certain Carrier place names for the various lakes in the Stoney Creek area and notes that many white people could not pronounce the names and so they became an anglicized version of native name. Explains the origin of the Bednesti Lake name

21’:55” Mary John explains about how liquor first coming into the territory and talks about how some of the men went on the train to join the war. She sings and drums a song called ‘Passenger Song’ and then explains the song

25’:43” Mary performs the ‘Four Winds’ song

26’:37” Mary talks about how the dancing had died out at Stoney Creek and c.1960 it was recommended that the dancing come back with a pageant to celebrate the 100th anniversary of missionaries arriving in their territory. The celebration was recorded on film. Talks about how dancing has been revived and now is taught to the children

30’30” Talks about the costumes made for the dancing. Talks about a moose hide she made for Eddie John

31’30” Bridget notes that Mary is now making a vest for Justa Monk who Bridget notes she has written a book about;

32:45” Bridget refers to the opening of UNBC and the coming of the Queen to open the University and how some native people in Prince George were against her opening UNBC

34’:40” Talks about the role of the Indian Agent historically

35’00” Talks about the role of policing in the native community and how to improve it

36’53” Bridget is recording Mary John outdoors at Lejac where they are looking at ruins of the old buildings. Mary points out the old Post Office building; Mary then shows the ruins of the old school and talks about segregation of the boys and girls at the school; she shows the play room of the old school; visits a cemetery and shows where Father Coccola is buried; then shows the buildings at Lejac old school buildings

Video temporarily stops

42’45” Shows Mary John back at her house in Stoney Creek

42’50” Bridget asks what is the most common question asked by people – of what do you want for your people – Mary states ‘hang on to culture and get an education”

43’40” Mary states that conditions have improved slightly [compared to 1976 at the time of Coreen Thomas’ inquest] but not to the level that she would like to see – as there are still alcohol, drug and unemployment problems

44’32” Mary notes that the preservation of the language has been ‘really good’ that the Elders are teaching other adults about their culture so that they can teach children; she notes that many Elders can speak Carrier really well – compared to the group noting at Metlakatla that not as many can speak their language.

46’00” Mary states there are many students at the [Yinka Dene] Language Institute; about 15-20 students

47’:24” Mary notes that ‘Potlatches are very important to our culture’ and that the Elders managed to save it

48’01” Mary refers to their road trip back from Metlakatla and their stop at Lejac. She talks about Lejac and how it is now destroyed – it would be better to preserve it and show what had happened there – Bridget compares it to the concentration camps in Germany and the preservation of those buildings to show the horrors of what went on there

49’13” Mary says she doesn’t dwell on the memories of LeJac – she had been there 72 years ago

50’00” Mary talks about the start up of the Potlatch House and the set up of a learning centre and the need to have it create work for the young people – Bridget notes that the potlatch house is now the centre of village activity

52’15” Bridget and Mary John reminisce about ’our’ book – and Bridget notes it was a ‘labour of love’ Mary notes that the book has made a difference – to treat First Nations people more like people – to show [others] [the impact] of racism

54’00” Bridget asks Mary to show the button blanket that Mary was given in Metlakatla and Bridget refers to the button blanket she was given as well. [The blanket is designed as a traditional Northwest Coast Button Blank; on the back of the blanket it is embroidered with beadwork in a circular pattern with the inscription ‘Keep the Circle Strong’ Bridget notes that the Elders there had a wonderful dinner for us as well.

54’58” Bridget videotapes Mary outside by the lake and she shows the outside of the log house which is the Potlatch House at Stoney Creek. She then shows the interior of the building which has photos of Elders on the wall.

Videotape ends

File consists of a Video 8 recording of Mary John in Metlakatla. : Bridget noted in a later 1994 interview with Bob Harkins that this road trip was conducted for Mary and her to attend the basic education class at Metlakatla. This recording has also been reformatted on DVD. This version of Mary John: Metlakatla is the original version filmed using a Video 8 videocassette formatted for hand-held camcorders. The version of Mary John: Metlakatla comprising 2008.3.1.202 is a master copy.

Videocassette Summary

Context: Video-recording conducted by Bridget Moran with Mary John on their road trip to Metlakatla to visit the Elders Group there.

Highlights Include:

0’:05” Bridget Moran records on videotape Mary John in New Hazelton at the road side

1’00” Bridget Moran records on videotape Mary John in front of the totem poles in K’san ‘Old Hazelton’ and note they are heading by car to Prince Rupert

2’00”At Metlakatla Mary is shown eating fried dried seaweed in a hall in Metlakatla with a group of people

7’:35” Mary discusses working in the hospital and financially having a hard time as her husband was out of a job due to change in logging practices. He had a difficult time being at home and Mary sometimes had to walk to work to Vanderhoof, a distance 9+ miles from Stoney Creek. Talks about a time of having to walk to work on the ice and put bales of hay in her boots to walk on the ice

10’:35” Talks about the difficulties of working in the white world

11’:15” Talks about the time that her son made his First Communion; priest offered to buy lunch for all the children; Mary remembers having him ask if she and her son could come into the restaurant as normally they were not allowed to go to the restaurants

14’30” Sandra explains how they had decided to invite Mary to Metlakatla; she had read the Stoney Creek Woman book and wondered if Mary was still alive; she called the Band office in Vanderhoof and was connected with Mary’s niece who asks if she would come to Metlakatla. And then decided to invite Bridget as well.

18’37” Mary talks about the origin of certain Carrier place names for the various lakes in the Stoney Creek area and notes that many white people could not pronounce the names and so they became an anglicized version of native name. Explains the origin of the Bednesti Lake name

21’:55” Mary John explains about how liquor first coming into the territory and talks about how some of the men went on the train to join the war. She sings and drums a song called ‘Passenger Song’ and then explains the song

25’:43” Mary performs the ‘Four Winds’ song

26’:37” Mary talks about how the dancing had died out at Stoney Creek and c.1960 it was recommended that the dancing come back with a pageant to celebrate the 100th anniversary of missionaries arriving in their territory. The celebration was recorded on film. Talks about how dancing has been revived and now is taught to the children

30’30” Talks about the costumes made for the dancing. Talks about a moose hide she made for Eddie John

31’30” Bridget notes that Mary is now making a vest for Justa Monk who Bridget notes she has written a book about;

32:45” Bridget refers to the opening of UNBC and the coming of the Queen to open the University and how some native people in Prince George were against her opening UNBC

34’:40” Talks about the role of the Indian Agent historically

35’00” Talks about the role of policing in the native community and how to improve it

36’53” Bridget is recording Mary John outdoors at Lejac where they are looking at ruins of the old buildings. Mary points out the old Post Office building; Mary then shows the ruins of the old school and talks about segregation of the boys and girls at the school; she shows the play room of the old school; visits a cemetery and shows where Father Coccola is buried; then shows the buildings at Lejac old school buildings

Video temporarily stops

42’45” Shows Mary John back at her house in Stoney Creek

42’50” Bridget asks what is the most common question asked by people – of what do you want for your people – Mary states ‘hang on to culture and get an education”

43’40” Mary states that conditions have improved slightly [compared to 1976 at the time of Coreen Thomas’ inquest] but not to the level that she would like to see – as there are still alcohol, drug and unemployment problems

44’32” Mary notes that the preservation of the language has been ‘really good’ that the Elders are teaching other adults about their culture so that they can teach children; she notes that many Elders can speak Carrier really well – compared to the group noting at Metlakatla that not as many can speak their language.

46’00” Mary states there are many students at the [Yinka Dene] Language Institute; about 15-20 students

47’:24” Mary notes that ‘Potlatches are very important to our culture’ and that the Elders managed to save it

48’01” Mary refers to their road trip back from Metlakatla and their stop at Lejac. She talks about Lejac and how it is now destroyed – it would be better to preserve it and show what had happened there – Bridget compares it to the concentration camps in Germany and the preservation of those buildings to show the horrors of what went on there

49’13” Mary says she doesn’t dwell on the memories of LeJac – she had been there 72 years ago

50’00” Mary talks about the start up of the Potlatch House and the set up of a learning centre and the need to have it create work for the young people – Bridget notes that the potlatch house is now the centre of village activity

52’15” Bridget and Mary John reminisce about ’our’ book – and Bridget notes it was a ‘labour of love’ Mary notes that the book has made a difference – to treat First Nations people more like people – to show [others] [the impact] of racism

54’00” Bridget asks Mary to show the button blanket that Mary was given in Metlakatla and Bridget refers to the button blanket she was given as well. [The blanket is designed as a traditional Northwest Coast Button Blank; on the back of the blanket it is embroidered with beadwork in a circular pattern with the inscription ‘Keep the Circle Strong’ Bridget notes that the Elders there had a wonderful dinner for us as well.

54’58” Bridget videotapes Mary outside by the lake and she shows the outside of the log house which is the Potlatch House at Stoney Creek. She then shows the interior of the building which has photos of Elders on the wall.

Videotape ends

File consists of a videocassette (VHS) recording of Mary John & Bridget Moran at the College of New Caledonia, March 12, 1991.

Videocassette Summary

Context: Bridget Moran and Mary John speaking to students at CNC, specific class unidentified.

Introduction: Bridget identifies that she will make the introductory speech and Mary will answer any questions because Mary doesn’t like to make speeches even though she is very good at it. Bridget’s connection with Mary and with Stoney Creek Reserve: Bridget Moran (BM) came to Prince George in 1954 as a social worker and soon after went to the Stoney Creek reserve. At that time the Indian Agent was in control of reserves and social workers were only called on to a reserve if they had to remove a child that was been abused or neglected. The state of reserves was horrible. BM made a promise to her mother that she would at some point do something about the impoverished state of reserves. In 1964 she was suspended by the provincial govt. for speaking out against current social policy. After writing her second published book Judgement at Stoney Creek she met Mary through Mary’s daughter Helen. Helen felt that Mary’s life was typical and yet a bit more significant than the average native woman and so approached Bridget to write a book about her mother’s life. BM put it off due to her busy career in social work. About 1983-84 Mary got sick and BM was afraid she wouldn’t have chance to capture Mary’s life story. So she took her motor home out to Stoney Creek and recorded Mary’s story – Mary beaded, while she knitted and they just talked. Once the book was written, BM’s daughter Roseanne became BM’s agent. After inquest in 1976 she had started 2nd published book Judgement at Stoney Creek but her publishers were not supportive of publishing books about Natives at that time. BM then wrote Stoney Creek Woman (SCW) and published it; after which time Judgement was better received. SCW now recommended in schools. Since publication they have done many talks across the province. Writing SCW was hard but wonderful in that Mary was able to share her feelings with BM. When the book was coming out Mary was very nervous, it came out on Nov. 12, 1988. Mary read the book and was really angry about reliving what had happened to her people. BM talks about thoughts of a 2nd book re: Mary’s thoughts on the environment and her culture. BM gives Mary the floor for questions.

[Note: most student questions were inaudible and so only replies have been noted below]

MJ: She was very upset about the Supreme Court decision. She speaks about how free her people used to be. They could stop and make camp anywhere – this was no longer the case as all is private property. There are greater alcohol problems in north. They are holding workshops in Stoney Creek to help the young people. The older people know what to do, beadwork, etc. the young people don’t like to do traditional tasks, even for cash. The elders try to teach them. She has about 5 boys working doing wood for elders but they have no axe so she had to get one for them They are so poor on reserves. The elders try everything – elders tried a wood processing plant - for 10yrs they studied this. Had people from Switzerland and Germany lined up who wanted the wood but they still didn’t get anywhere.

BM: People are now living better in Stoney Creek. When she first visited a reserve tuberculosis (TB) was rampant. In 1954 so many people had TB and they were all treated away from home. This left people at home (mainly women) to raise the children by themselves. We have social network now that was not existent in ’54. Still compared to the majority of society, reserve conditions are comparable to living conditions in the 3rd world.

MJ: Some reserves like Ft. Ware are just desperate. One night staying in a medical house, a child 10 or 11 was wondering around at night in the rain. When they got up in morning and he came into the centre and had breakfast. They asked him why he was outside all night. He said he was trying to catch horses. This boy was enamored with the cowboy hat and leather jacket another boy there was wearing. This other boy told him he would buy a hat and coat for him when he returned home. By the time the package was sent, the young boy was dead from sniffing gas.

BM: People are depressed and alcohol and drugs is one way to cope

MJ: Men drinking early in morning, she talked to them. One guy hadn’t worked a day in his life. She asked him why he drinking. One guy says he just drinks once and awhile that is wasn’t a problem. The other guy left as didn’t want to hear the truth. She says they need a job – something to live for.

MJ: She tells children to get educated and then come back to the reserve and help their people - like Eddie John and Archie Patrick did. [Discussion on environment]: The Elders group comes together and talks about environment: how the earth is being stripped dry. This worries them. The animals are not there. Years ago, they were so poor, they just had basic food. Their cupboard was in the bush, they were so busy trying to make a living while the men were out logging trying make money. The men logged by hand and the land still looks untouched. That is how they earned a living, and the land is not scarred.

Years ago people were not fearful of sickness, there was no sickness, and there were hardly any accidents as everyone was so used to the bush. The only thing her people feared was starvation. After the 1918 flu many orphans were left. One old lady took them in and had hardly any food herself. In the spring she had a cache in ground she had buried there. She sent 2 children to it to dig it up. When the children brought the supplies back to camp the old woman gave ½ fish to each child. They were like hungry dogs. The elders keep telling people, when hunting/fishing don’t waste anything in fear of starvation. One old lady said they were starving and went into bush and found mouse droppings and even that they cooked. With a moose, you eat all of it, right down to the marrow.

MJ: The elders organized themselves and did workshops to learn how to help their young people. Many deaths among young people.

BM: Suicide rate among natives is 2-3x’s higher than among non-natives

MJ: The elders have tried everything to help with the problems of young people. But the youth drift away as they have no interest.

BM: One of the psychiatrists she talked to said that one of the best preventions for suicide is for kids to have a goal to work towards. Native youth have no goals, no education, no jobs, nothing to look forward to.

MJ: Her daughter doesn’t like to be on welfare. She was searching for job. The Elders gave her a job watching over traps but this had to be shut down due to lack of money for furs. She then put her name in as a janitor for the highschool in Vanderhoof but was turned down. MJ furious because they [the white people] in that school wouldn’t even let her daughter clean up their shit!

BM: Northern communities with large native populations, like Fort St. James or Vanderhoof, rely on the money brought in by the native community; yet most businesses don’t employ natives. The natives have to realize their own economic power.

MJ: The elders started a bingo night and were going to hold a fishing derby. They sent a young man into Vanderhoof to find donations for the derby. He went to the Elks club and was told he’d get nothing there because Stoney Creek took away their bingo night. Her people had supported them [the Vanderhoof bingo night] for years and years before, but as soon as the natives had their own bingo night they were not supporting the one in Vanderhoof anymore.

MJ: She told her husband she was going to PG to talk about the book. He has no problem with it.

BM: Lazare doesn’t read or write.

MJ: He went to school at Lejac for 2 years. Now all he can do is sign his name. It’s sad.

BM: Joanne Fisk just completed PhD, she teaches at Dalhousie but she used to spend summers in Stoney Creek and she did her thesis on Lejac. Her thesis was that residential schools were of some help to girls but were disastrous for boys. The girls learned to read and write; while few boys came out of residential schools who could read or write. All they did was hard work out in the fields. When preparing for Judgement, she spoke with Coreen Thomas’ father. He attended Lejac for 6 years, he was beaten and worked like a horse, and he couldn’t read or write. He cried for 2 hrs when BM told him she was going to write a book about his daughter. Sophie Thomas, however, felt she learned a lot out of Lejac – how to sew, read and write and make bread. Men learned nothing to help them make a living.

MJ: Last fall, there was a conflict between town and reserve children. Vanderhoof citizens didn’t want reserve children attending the town school. It cooled down. The school on reserve only teaches kindergarten, and grades 1-3.

MJ: Her daughter-in-laws, Gracie and Mary are teaching. The elders are going to have a summer camp at Wedgewood fish camp. It is going to be a survival camp.

MJ: They have dancers. They try to revive the language and culture. There aren’t too many storytellers. Selina and Veronica are two elders who are good storytellers. She’s going to try and get hold Veronica and tape one of her stories, she has taped 3 of them already. The elders are training the teachers (of language) and working on dictionaries and some books.

MJ: The population on her people is about 500 and increasing. Most people are out in towns, like Vanderhoof, and PG. There are about 400 people living on reserve but housing is really bad.

MJ: She says her people were trying to get a grant to get money for wood processing. The Swedish people had their own plans. There was a place on reserve with a railroad that was all set up for wood processing but the DIA had a problem with the funding. The band hired a consultant in Burnaby to put their proposal together. The DIA said they would hire Price Waterhouse to study the study the band produced and there it stayed.

MJ: Her son Ernie started logging on the reserve in ’78 or ‘79. He hired boys from the reserve. Somehow DIA got in and said his work was a conflict and that he couldn’t log on reserve. He already had all the heavy equipment. Her son-in-law, a white man, a businessman living on reserve had helped Ernie to get all this machinery. After the DIA came in, they took this logging business away from him, he lost his machinery. He was so desperate, she thought he would commit suicide. He left for Fort St. James. She was so worried. The DIA needed him to sign some papers but a friend they had within the DIA told Ernie not to sign these papers so Ernie ran. Mary was so angry at the DIA she felt ready to kill, she even had a big rock in her hand when the DIA came looking for her son. Her daughter told her not to do it. Ernie refused to sign. He lost all the machinery. That is where the DIA puts us.

BM: CBC did a series after Oka, looking at Natives across the country trying to start businesses, and in every case they were sabotaged. As long as natives are poor and uneducated, a lot of people in DIA have good jobs.

MJ: Reserve stories pretty hard. Her people tried ranching, they had 150 head of cattle. Years ago an Indian agent, a good man, told her to start ranching on reserve. He’d give them so many acres on CP land

– “certificate of possession”. Some people still have CP land and they can do what they like with it, but they can’t sell it.

BM: There are divisions among natives. She was interviewed by reporter to talk about how there wasn’t one cohesive voice speaking for all natives. She said that was hard, and that natives, as with white people, don’t speak with one voice – just look at the Legislature. Different groups among natives? Of course.

MJ: Years ago, one family lived in one house and got along. It is not the same anymore - family separates so much. Children are taken away. When she got married she lived with 3 families in one house. Long ago there would live one clan in one long house and everyone got along.

MJ: In 1970, her people were allowed to send children to catholic schools in town only. The children were not allowed in public schools. So she went to Ottawa to lobby for the freedom to send native children to any schools they want. She talked to Chretian, the then Minister of Education. Since then they have had that freedom.

MJ: Some families have tried everything: Christian schools, public schools. She’s not sure where they are sending children now - public school is a bad influence! (laughs). Families often sendthei children to Christian schools. There is a high drop out rate. She’s not sure why. In public schools children have choice of what to take. Young people are not “with it”. When children graduate…she took some teenage dancers to Missouri one year. She asked these children where they were, and some said USSR and she says they are not “with it”. They didn’t know anything about the country they were in.

BM: Recently she spoke with teachers and found out that 20% of students at PGSS are now native and yet there is not one native teacher. She found in last 5-7 years, more native people have been coming to PG so as to give their children a better education. But the education system isn’t supportive of them and their children go under. There is one native counselor at PGSS - that’s it. Teachers they talked to spoke to Mary about the differences and frustrations they had with the way native children were raised; such as how native children will look at the floor when speaking to teachers and will then get into trouble.

MJ: Children are taught not to look into eyes as this is like a challenge to the person speaking. They must look down at their own feet and humble themselves. That’s a problem. She says they have to trust [the teachers?]. When a native student is in school and having problems, it helps them to be able to talk to another native person.

MJ: Trust is hard with white people.

MJ: As long as there are reserves, people stay on reserves. Natives get lost in society when they go to towns.

MJ: She will go anywhere to get what she needs from the bush. In the bush she feels close to the earth and at home, she doesn’t feel that way in PG.

BM: Mary and her went to Vancouver in the spring of ’89. Mary stayed with her daughter-in-law at UBC and she couldn’t wait to get back to reserve to find something to do!

MJ: She couldn’t do anything, it was just like a chicken coop. You can’t work outside. She would die if had to stay in a place like that.

BM: The chances of native culture surviving is so much better now than it was 30-40 years ago. It came close to dying out. There is now a pride in being native and an interest in being native that wasn’t there when she started in social work. Back then people were almost ashamed of being native.

MJ: She agrees with Bridget. Many times she was ashamed of her food, the way they talked, everything was against us. Many young people she speaks with are coming back to reserves. In the ‘20-‘30s, her sister-in-law married a non-status Indian and from then on felt she was different because she could go to liquor store, etc. She became ashamed to be seen with Indians. She wouldn’t talk to them on street but would accept them in her home.

MJ: In the potlatch system, her sister-in-law is a higher rank than she is. It would cost MJ a lot of money to raise her status within their clan system. Her sister-in-law is a spokes person in their clan but she had to pay for it. She was given a name and a song. She has to look after her behaviour and all that. She asked Mary to make a blanket for her son many years ago. MJ had been watching him and he wasn’t behaving well. Finally she made that blanket but for another person because he wasn’t ready. He has to behave himself.

MJ: Her children would take her clan, not Lazare’s clan. You cannot marry into your own clan – they are like brother and sister, if that is going to happen they have to separate from the clan.

MJ: They are trying to include all young people. They have a white man married to a native girl, who is very active with the elders and he is a drummer now. They are going to initiate them into her clan.

Another one is also very good with elders. His grandfather is pure Indian but married a white women and so lost much native blood. But now he wants to learn all about his culture. She has all his grandfather’s regalia as he had no one to receive it, but she intends on giving it to his grandson.

BM: The culture is still alive at Stoney Creek. Things are still done in the old way. It is sad that the non- native world cannot see this culture alive.

MJ: If you have a problem, you would ask the family in opposite clan to help you. Such as money for a sick child to go to Vancouver for operation. Or with a funeral, like when her daughter Helen died, people helped her. People helped out while she was watching daughter in hospital, then they paid for the funeral. One year later, her clan put up potlatch and paid back all that was done for her family. In the clan system there is always someone to help.

BM: At the potlatch she attended their were clan members that came from all over BC

MJ: No negative things came from publishing this book. Although one doctor, Dr. Mooney said there wasn’t separate wings for whites and natives at the Vanderhoof hospital. But she remembers this as so.

BM: As a social worker she saw separate wings. She only had one negative encounter with Dr. Jolly – a good friend of Mary’s and of the native peoples around Stoney Creek. She went to Nanaimo for a signing and saw Dr. Jolly there. He said he was angry about the book and wanted to know why, if there was racism, didn’t MJ go and talk to someone. BM asked him who MJ would talk to, the Mayor? She explained that when you are repressed you don’t feel you can go and talk to someone in power. He felt Stoney Creek had been so wonderful for him and the knowledge of this racism distressed him. With her second book, nothing bad yet has come out of it, yet she’s heard nothing really out of Vanderhoof. Most people accept that there is racism and take it from there. Going to Vanderfhoof with Mary is like going to Vanderhoof with royalty. Her own reserve is also very proud of her.

MJ: Indian people are very shy and she wondered how her people would react to the book. Everyone who read the book liked it.

BM: 100’s of people told her that after reading the book they just didn’t realize the situation. Mary’s life has then broadened their understanding of what it meant to be native and a native woman.

MJ: She speaks to her sister-in-law or Veronica about the old days and the young people.

MJ: The reserve has a special constable from the Queen Charlottes who comes and visits her all the time. He is native but he is scared of the Carrier people. She tells him he is welcome, and to feel at home. His boss had told him to go from door to door on the reserve to see who’s living there. He doesn’t want to and she tells him not to, unless he’s asked in. His boss came to see her. She told him that plan wasn’t good and he listened.

BM: Mary has a daughter-in-law who is in the RCMP in Ft. St. James.

MJ: She was in Vancouver working in dispatch. She came home, but now she’s in Regina for more training.

MJ: Her people still have the RCMP out for salmon feast every year. They like it better at Wedgewood. She cooks bannock over the fire.

Instructor: Thank you very much.

Clapping from audience.

File consists of documents related the May John and "Stoney Creek Woman" including a laser copy of a group photograph featuring Lazare and Mary John, Bridget Moran, and Justa Monk, a programme for memorial service held in honour of Lazare Peter John (Thursday, April 11, 1996), "An Elder's Message: Address to the Western Consortium on Aboriginal Languages by Elder Mary John OAC" (Yinka Dene Language Institute, Annual Report, Spring 1997), a faxed formal announcement from Arsenal Pulp Press re: publication of a new edition of Stoney Creek Woman (June 11, 1997), a photocopy of Saikuz Cookbook: Sharing Our Cooking Culture (1984), and "Environment Presentation" by Mary John Sr. (May 29-30, 1997).

Close view of Mary John. Plant, couch, and window in background.

File consists of photocopies and original newspaper clipping: "Story of survival still lives on" (The Free Press, Aug. 17, 1997), photocopies and original newspaper clipping: "Stoney Creek Woman named as a member of Order of Canada" (The Citizen, Jan. 10, 1997), photocopies and original Guardian newspaper containing article "Top honour to Stony Creek elder" (May/June 1997).

Audio recording consists of an interview conducted by Bridget Moran with Mary John.

Audiocassette Summary

Scope and Content: Tape consists of a recording of Bridget interviewing Mary John primarily about her visit to the former native village site of Cheslatta

Side 1

Interview in process

00’05” Bridget interviews Mary John, Mary is referring to Madeline her niece.

1’00” Bridget asks Mary what made her decide to go to Cheslatta – to see the site where she had lived. Bridget asks if it was a ‘rediscovery’ trip. Bridget asks if this is where the village was burned out and flooded out [by Kemano development] Mary talks about her son Ernie wanting to go there and create a territorial hunting ground. She talks about going there with her niece Madeline and Alex

8’40” Mary explains how they got to Cheslatta; the travel there was by van through Francois Lake and via logging roads; it took about hour and half drive

11’00” Mary explains it was not the village that had been flooded that they went to; not the original village; she notes there was a campsite set up for them but it was cold at night. There were people there from Stellaco, about 75 total. She describes making bannock on a stick over the fire ‘the real bannock’ for the youth – like an “Indian pizza” (she laughs)

16’00” Mary continues to talk about the activities that she did at Cheslatta; show the youth how to fish, spear fish, clean fish, cut in strips and smoke the fish. There was no smokehouse but they created a lean- to and smoked the fish. Mary also notes another day Mary and Madeline took the youth to the bush and talked to them about uses of trees –

22’00”-20’25” Mary describes the steps involved with showing the youth at the Cheslatta camp how to collect spruce in order to build a smoke house for smoking the fish

29’30” Mary discusses food that she prepared for the gathering for the people

31’00” Mary talks about the group visiting the old village Cheslatta after the gathering

Mary then leaves to attend to a crying baby [a great-grand-child?]; they greet the mother

33’00” Bridget refers to a group of kids she talked to at Kamloops about their book Stoney Creek Woman. Bridget tells Mary she has letters written to Mary John by several students who had read Bridget’s book that she wants to show her

36’00” They continue to talk about the former Cheslatta village and what the former village residents want to do about the village; Mary notes there are archaeologists working there. Mary states the people have not yet received compensation for being taken off their land. Bridget notes those people loss their sense of community

38’31” Mary remarks the people at Cheslatta “have a good chief” “very humble person”

39’40” Bridget asks Mary about the Lejac pilgrimage. Mary then talks about the pilgrimage that is held at Lejac and that she had just been there ‘on Sunday night’; she notes it is arranged by Celina; she notes there were Tache people there. Bridget asks if there are children buried at Lejac and Mary notes there are children and students buried there – about 15 to 20 buried there.

43’00” They briefly discuss if this was a rediscovery for the Cheslatta people at the event. Mary agrees; she notes she stayed there for 10 days; Bridget remarks it was similar to Mary’s former camp of what she had experienced at Wedgewood. They talk about Mary’s son Ernie and that he has in Bridget’s view ‘leadership qualities”

45’30” Bridget asks about getting a bannock recipe for a Senior’s cookbook. Mary begins to tell the recipe

Side 2

47’40” Mary continues to show Bridget how to make bannock

50’00” Mary briefly refers to the event at Cheslatta again

End of tape

Audio recording consists of an interview conducted by Bridget Moran with Mary John.

Audiocassette Summary

Context: Tape recording is an interview between Bridget and Mary John in which Bridget initially asks Mary John about events after the inquest into Coreen Thomas’s death. Bridget notes also that she wants to provide an update on Mary John’s life 10 years after the inquest.

Side 1

00’05” Bridget asks Mary John about her role in the Coreen Thomas inquest. Mary thinks that she discovered Coreen’s death due to the ringing of the church bells [to announce a death]. She tries to recall the series of events leading up to her time being involved in getting an inquest. Recalls Sophie Thomas’ desire to have an inquest into her death

6’00” -10’00” She recalls that the [Indian] Homemakers Association became involved in attempting to get an inquest. She says ‘she was just tagging along with it …I was not a fighter” Bridget notes that Harry Rankin stayed at Helen’s house when he represented the Homemakers Association at the inquest. Bridget recalls the ‘marvellous’ dinner that was put on for them at the time of the inquest by Mary John and Helen. Mary John notes it was at the invitation of the Homemakers Association for the group to come to her house.

10’:00”-14’00” Bridget and Mary talk about follow-up to the inquest and Coreen’s family.

14’50”- 25’00” Mary talks about her involvement as well as others in the creation of the Elders Society after the death of Mary’s son due to drowning in 1978. The Society had workshops in an effort to revive their culture with the hope of having the younger generations take pride in their culture. One of the activities was the building of the Potlatch House in 1980 where they did traditional activities including tanning of hides.Talks about acquiring the land to build the potlatch house and having the Chief take care of getting the land from BCR; the Society cleared the land twice over to set up the house. Mary explains that the Society acquired funding of $93,000.00 from ARDA [?] to clear the land from the logs and build the house.

26’00”-30’00” Mary talks about a new project that the Society has to build 10 rental tourist cabins as a business for the youth to operate. Bridget suggests it could be similar to that at K’san. Mary also explains that there is a cook-house at the Potlatch House as well and that it has been used for community events, weddings, dinners, organizational events also.

Tape stops momentarily and starts again

30’05”- 36’00” Mary talks about the drowning of her son and finding of his body in 1978 as well as other tragedies that happened in the community which led to the creation of the Elders Society to assist the youth

36’30” -39’30” Mary talks about the joys of finally having her own house and the building of the house

39’32” -42’40” Mary talks about the organizations that she is involved in now. She talks about a film made in the community about social workers coming in the community to work with Elders to care for issues related to youth. She notes that ‘that’s when the ice broke’ and it made a difference.

43’00” She talks about a dinner that she holds every year for the police officers to thank them for the service they do for society

43’30” Talks about fishing at Fraser Lake

44’00” -46’00” Mary talks about her work now at her house to teach the youth about their culture: making of baskets, moccasins, tanning of hides

End of side 1

Side 2

46’30”-48’00” Mary continues to talk about the activities that she does with native youth to educate them about their culture

48’50” Bridget asks about whether the youth are involved in tree-planting and asks another woman in the room (Bernice?)

50’00” – 56’00” Bridget asks what her three wishes are for her people: better lives; more education for the young people to have better jobs; they need to get out to the white world and not be so isolated; she refers to when she worked in ‘the white world’ She talks about the isolation of the reserve and yet the protection that it offers to the people as well. Bridget and Mary talk about the reserve offering a way to protect the native culture. Bridget asks why it is important to protect their culture. Mary notes their culture is so important; she notes that other cultures like Japan and China haven’t lost their culture so why should the natives.

56’05” Mary notes that none of the grandchildren speak Carrier and the need to protect their culture and language when being surrounded by a white community. Refers to her grandson Fabian who is in the room

57’00” Bridget recalls a Fort St. James woman who tried to keep native kids out of white schools. She wanted them to be kept on the reserve so that they didn’t lose their culture. She talks about the fight by many to get their native status back – those whose one parent is not native

58’00” Mary talks about her worries for the young native people in the community who fear they have no future and who have no employment or education.

End of tape

File consists of chapters 1-9 with revisions input.

File consists of drafts of manuscript "Mary and Me" by Bridget Moran [print outs generated by Archivist].

File consists of a draft copy of manuscript "Mary and Me" by Bridget Moran.

File consists of 1 CD-R entitled "Mary and Me" Fujifilm, 80min/700MB CD-R and printouts from CD-R including drafts of manuscript "Mary and Me" by Bridget Moran [print outs generated by Archivist from CD-R].

File consists of:

- Job 01-09 - original scans ; Chap 01-19 (no 16, 17, 18) edited version (July 27) [Floppy Disk - AT&T IBM Formatted, 2HD]

- Drafts of manuscript "Mary and Me" by Bridget Moran [print outs generated by Archivist from floppy disk].

File consists of a videocassette (VHS) recording of Mary & Lazare John’s 60th Anniversary Party.

Videocassette Summary

Context: Celebratory events for Mary and Lazare John’s 60th Wedding Anniversary, 1989.

Introduction: Party held in an auditorium. Head table in front of a curtained stage, decorated with a blue tablecloth. Streamers and pink, white and blue balloons provide a backdrop for the head table. Silver paper bells decorate the front of the table with a larger “60” sign on the front centre of the tablecloth. There is a large wedding cake situated between Lazare and Mary on the centre of the head table. Pink and white balloons and streamers decorate the walls of the hall.

Stoney Creek dancers (children of all ages) come to the centre of the dance floor to perform. Fifth dance is performed [video captured dance halfway through] to drumming and singing accompaniment. Sixth dance (inaudible title) is performed. Guests of all ages join in including Mary and Lazare. Seventh dance is called the “Chicken dance” where the boys are the roosters and the girls are the chickens. Eighth dance is the “Farewell dance”. A thanks goes out to the party guests for watching the dancers.

Various unidentified guests come to the back of the head table to wish Mary and Lazare their best.

Dan: He had heard about Mary and Lazare’s hospitality from Helen and (?) Prince. He and his family came to visit. They spent the night on the John floor. Mary helped his family and a young woman named Janai get a place in the Potlach house, and then on to the schoolhouse where they all spent the summer. (This family worked for a gospel mission). He spoke of the young woman named Janai who was now married to a Fijian and who would’ve loved to have been at their anniversary. He also introduced people from Wisconsin and from Fiji. The Fijian guests were going to perform some songs that expressed their connection to God. He congratulates Mary and Lazare on the 60 years together and again thanks them for helping opening Stoney Creek up to their missionary work.

Fijian guest sing several songs to an acoustic guitar and dance several dances to tape recorded Fijian music.

Unidentified woman from England and now in Thunder Bay says thank you to Lazare and Mary who allowed her stayed with them and their family for a time.

Unidentified man on guitar and woman sing a song for Mary and Lazare at the front of the head table.

Unidentified man with guitar sings a Johnny Cash (?) song at the front of the head table (song dedicated to a cousin from Sechelt). (“Big city turn me loose”?) Man sings second song originally by Randy Travis. He then plays guitar while two other unidentified men sing Hank Williams Sr. “There’s a Tear in my Beer”.

Unidentified woman sitting at front playing accordion while Winnie sings “Memories are made of this” (?)

End of tape

File consists of a videocassette (VHS) recording of Mary & Lazare John's 60th Anniversary Party.

Videocassette Summary

Context: Celebratory events for Mary and Lazare John’s 60th Wedding Anniversary, 1989.

Introduction: Party held in an auditorium. Head table in front of a curtained stage, decorated with a blue tablecloth. Streamers and pink, white and blue balloons provide a backdrop for the head table. Silver paper bells decorate the front of the table with a larger “60” sign on the front centre of the tablecloth. There is a large wedding cake situated between Lazare and Mary on the centre of the head table. Pink and white balloons and streamers decorate the walls of the hall.

The party begins with a prayer – the focus is on the head table. Guests seated at long tables are passing along the food, eating and talking. The camera pans in and out to the head table and surveys guests.

Mary and Lazare’s daughter, Winnie, stands behind the head table and addresses the guests. She tells a joke about her parents and then goes to sit down.

An unidentified man approaches the head table and pours drinks for those seated there.

Edward John approaches the head table and shakes both Lazare’s and Mary’s hands. He then talks with them and other guests at the head table for quite awhile.

Young people approach the head table and take photographs of the anniversary couple.

An elderly woman speaks briefly to Mary and Lazare from behind the table. Another woman in a wheelchair speaks to Mary and other guests at the head table.

Edward John (EJ) – EJ introduces himself as the MC and speaks at back of head table to the guests. He asks for round of applause for Lazare and Mary for being able to live with each other or 60yrs. The day they were married, they had no wedding cake, so the cake on the table is to make up for that. 60 years ago, Lazare never said “I do” at the ceremony and Mary is still waiting. He introduces their 9 children from their marriage included the 2 that died: Helen, who was active in Stoney Creek affairs, tribal council and Indian Homemakers Assoc. of BC and Charles (don’t know too much about him). He then introduces the children still remaining: Winnie, Bernice, Florence, Ernie, Gordon, Johnnie and Ray. The anniversary couple have 32 grandchildren, and 25 great-granchildren: many children, grandchildren, great grandchildren. Before asking couple to cut their cake, he introduces speakers. First up is Aileen Kimble (AK) from Vanderhoof.

AK: Friends with the couple for many years, happy anniversary Lazare and Mary.

EJ: No set agenda for this event, just time to celebrate and spend time with the couple. There are 30 people from Sechelt (nieces and nephews) that came up for this event: Valerie and Ken, Randy and Lani, Audrey, Willard, Janice, Bradley and Leonora, Wayne, Rena and Earl, Clarke. (applause) EJ calls on Bridget Moran (BM) to speak.

BM: Told a story about Mary’s wedding day, and when she first came to Stoney Creek. She touches a bit upon Stoney Creek Woman.

David: Tells a story about trapping with Grandfather Lazare. He thanks everyone for coming.

Winnie: Thanks siblings and Dorothy MacIntyre for helping her decorate the “leaning tower of Stoney Creek”. Also thanks Adela and Nicholas George for decorating the wishing well.

EJ: Mary’s cousin from Prince Rupert George and Emily Bird recently celebrated their 50th (?) wedding anniversary. Long time friend is Selina John (SJ), elder to tribal council called to speak.

SJ: She is so happy to be sitting next to sister-in-law. Ever since they both married they worked together. Raising their children together, they were like one big family. Not one cross word between them in 60 years. They’ve been through a lot but one thing stands out – during the day they took care of family and if they had time they would hunt squirrel in the bush. One time they were hunting squirrel and they got lost and it took them forever to find their way home. They came home hungry, frozen and tired and met with husbands who were furious because they thought they had been chasing boys. She talks to young people about the example Mary and Lazare’s marriage should be to the whole community- 60 years they’ve been together. The young generation of today, each walks in their own direction. If you want to have a good life you have to work at it. Marriage is a contract. If you marry you have to work towards it. She’s very proud of her sister-in-law, many times SJ was down especially after her husband died and MJ pulls her up. She wishes Mary and Lazare many more anniversaries to come.

EJ: Calls Sophie Thomas (ST) to say a few words.

ST: Wishes the couple a happy 60th anniversary and many more. She worked together with Mary for the people on reserve. Since they started the fought for running water, now they have sewer.

EJ: Calls Veronica to say a few words.

Veronica: She very happy to be there- to see Mary on her 60th wedding anniversary. It isn’t easy. Mary has faith in the Lord. She didn’t forget her mother’s and grandmother’s words. You have to listen when an elder talks to you. People come to elders for advice and direction and spiritual words too. So it is nice to see Mary and Lazare reach their 60 years of marriage – this is a very holy thing. Holy matrimony is important to keep. She hopes the young generation will take an example from Mary. It is not good to divorce. Always pray. She thanks many people for coming. May the Good Lord look after you wherever you are.

EJ: There are a few more speakers, elders mostly. Mary Pius (MP) from Heightly (?)

MP: Her Aunty Mary and Uncle Lazare have done so much for the people of Stoney Creek. Mary was one of last midwives. She took the baby into world and would help nurse along the young mothers too. Now you have nurses, doctors, hospitals, but we still have to work just as hard to keep the young mothers going. The young generation is still here because of the hard work of Mary and Lazare. We thank them for all the hard work to keep the young ones going. They take care of those who are sick, and help supply Indian medicine. She hopes the good Lord will reward her aunt and uncle and wishes them the best from the Holy Spirit. She wishes good luck to her Aunty Mary and Uncle Lazare.

EJ: There are a couple more speakers, then cutting of the cake, then a 60th anniversary waltz and some entertainment. EJ calls Justa Monk (JM), who has worked with Mary at tribal level carrying on business through the whole tribal area, and who has been deputy chief, past tribal council president and chairman.

JM: In the short time he has known the couple, he has learned many things in his culture and about society today. He is honoured to be there sharing their food. He talks about Lazare’s speaking in church. What they have done in Stoney Creek has spread to other reserves like his. He wishes them well.

EJ: When the couple married 60 years ago, they didn’t have any money. They borrowed $25 from his brother. Lazare went to work and Mary worked too. Lazare worked at a railway tie camp. EJ calls on Evelyn Louie (EL) to speak.

EL: She’s really happy for the couple. She thanks them very much for everything.

EJ: Introduces Ellen Lasert from Burns Lake

EL: She is an apprentice under Mary John. Mary has been an inspiration to her and she brings greetings from people in Burns Lake and Chief (?) Charlie.

[Winnie speaks to Edward John]

EJ: Calls on Cecile Patrick to speak.

CP: She wishes her uncle and auntie a happy anniversary from their family. Thanks everyone for the food and effort in preparing food. She is the second eldest daughter of Lazare’s sister.

EJ: Comments: Lazare and Mary’s doors in Stoney Creek are always open. Every time you visit you are always treated with respect and made to feel at home. He has these wonderful memories of this couple. She always has her smokehouse and her wood fire going all the time. She always has tea ready. He asks Lazare and Mary to cut the cake for the 60th wedding anniversary.

[Lazare and Mary pose with a knife ready to cut the cake. Guests rise to take photographs. Then Mary rises again and tries to remove the cake topper and cut the cake for her guests but it doesn’t cut easily. They are finally told there is already cake for the guests in the kitchen.]

EJ: Calls on Bob Holmes (on piano?) and Jen Hoffner (on accordion) to come to the front.

The recording breaks and screen goes black for a second

Picture resumes and Lazare and Mary are seen doing the anniversary waltz. They dance for a bit and then sit down, but another gentleman takes Mary up front again to continue dancing (a son?).

EJ: Announces the entertainment: the young dancers from Stoney Creek and the PG dancers. He calls dancers to the floor; while waiting he tells a story about a blind snake and a blind rabbit.

Drummers gather and begin to play and sing. Stoney Creek dancers (children of all ages) come to the centre of the dance floor to perform. Second dance is called the “Beaver Dance”. The third dance is called the “ -inaudible- Dance”. The fourth dance is called the “Four Winds Dance”.

Tape ends.

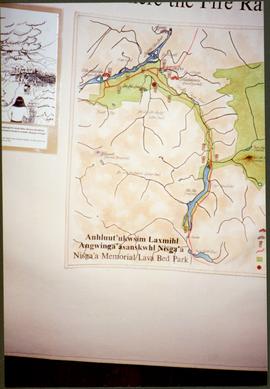

Photograph depicts colour map displayed in unknown area, second poster semi-visible on left. See item 2008.3.1.22.34 for image believed to depict lava bed.

File consists of a letter from Jean Y. Wright, Managing Editor for Chatelaine magazine to Bridget Moran re: letter of rejection for manuscript on childhood memories (July 21, 1976); including typed manuscript.

File consists of the manuscript of A Little Rebellion by Bridget Moran.

File consists of the original manuscript with some yet to be included edits.

File consists of the manuscript of "Judgement at Stoney Creek" (101 pages).

File consists of "Manner of Life in Ireland" by Bridget Drugan, Feb.5, 1941 (original handwritten story and photocopy).

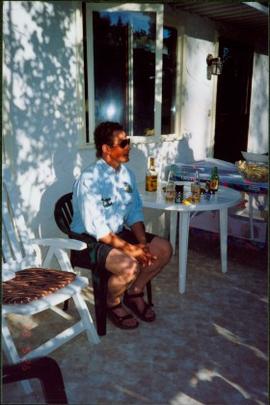

Photograph depicts Dave seated in lawn chair on deck in backyard. Chairs and tables set with food and beverages are also visible on deck. Accompanying note from Maureen Faulkner: "Dave looks on... He wished he'd been able to attend the ceremony. Next time?" Photo taken on the day Moran received an Honourary Law Degree from the University of Northern British Columbia in Prince George, B.C.

File consists of a copy of fax sent to Kent Patenaude from Anja Brown re: Bella Bella meeting with Legal Services (Sept. 14, 1998); a fax copy of LSS News featuring article on Bridget Moran (Sept. 24, 1998); a fax of email sent to Kent Patenaude by Dennis Morgan re: Alert Bay meeting (October 6, 1998); a memo to Notes on File from Kent Patenaude re: Community Consultation - Alert Bay (Oct. 7, 1998); and the Native Community Law Office Association of B.C. Newsletter (August, 1998, Vol. 1, Issue 1) including: draft copy of letter written by Bridget Moran to the Editor (Sept. 25, 1998).

File consists of:

- Thank you cards to Bridget from various offices

- Letter from Bridget Moran to Pindar [?] re: closure of LSS Langley office (Sept. 19, 1997)

- Official appointment announcements from Mike Harcourt (1995) and Glen Clark (1997) recognizing Bridget's appointment as a director of the Legal Services Society

- Copy of "Endorsement #8: Specific Claim Exclusion" issued to the Legal Services Society by American Home Assurance Company (March 1, 1997)

- Letter to Bridget Moran from Ujjal Dosanjh, Attorney General of B.C. appointing her to the position of Director of the Legal Services Society of British Columbia.

- Copy of Order of the Lieutenant Governor in Council (June 11, 1997).

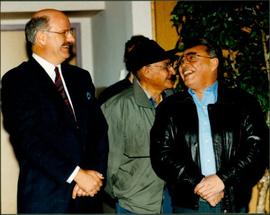

Handwritten annotation on recto: "His Honour David C. Lam congratulates Bridge Moran of Prince George for her award winning book - Stoney Creek Woman." Lieutenant Governor Lam stands in formal attire on left, presenting medal to Moran. Two woman stand in background.

File consists of:

- Correspondence between Harry Rankin and Bridget Moran re: her suspension (1964-66)

- Copies of correspondence from W.B. Milner to Harry Rankin (1967)

- Copies of correspondence between the Civil Service Commission and Harry Rankin re: Bridget Moran (1964-1965)

- Handwritten copies of correspondence between Bridget Moran and W.H. Dallomore (?) re: potential employment (June 21, 1965)

- Copy of Bridget Moran's Oath of Allegiance; Office and Revenue to the Government of the Province of British Columbia (Dec. 20, 1951)

- Copies of correspondence between the Civil Service Commission and Bridget Moran (1965)*Copy of letter to Hon. P.A. Gaglardi from Bridget Moran (Feb. 17, 1968)

- Newspaper clippings from the following newspapers: the Sun; The Vancouver Sun;

- Copies of correspondence between Harry Rankin and the Social Welfare Department (1964)

- Draft version of Bridget's application to the Civil Service Commission calling for a review of her suspension.

- Letter from E.R. Rickinson, Deputy Minister of Social Welfare to Bridget Moran, (Jun 15, 1965)

- Copies of correspondence from Bridget Moran to W.B. Milner (1966).

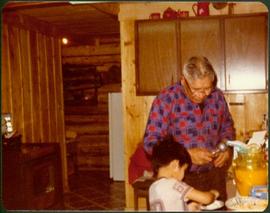

Photograph depicts Lazare John (husband of Mary John) dishing ice cream onto plate of pie. Young boy in foreground, kitchen and hallway in background.

Photograph depicts unidentified building with large wood beams in entryway.

File consists of:

- Author Reading and Autograph Session with Bridget Moran at the Nechako Branch of the Prince George Public Library.

- Author reading by Bridget Moran at the Dease Lake Library (Oct. 16, 1995)

- Hillbilly Literary Nite presented by Culculz Lake Literary Club and featuring reading by Bridget Moran

- Author reading by Bridget Moran at the Valemount Public Library (May 10, 1996)

- Author reading by Bridget Moran at the Tillacum Library

- "Bestsellers" (Jan. 21, 1998) ; [Bestseller's list for non-fiction] The Vancouver Sun (June 17, 1998).

File consists of:

- Everywomans Books 20th Birthday Party Celebration, 1975-1995 featuring an advertisement for a reading Bridget Moran

- "Together again..." by Martha Perkins, 2 pages (Haliburton County Echo, June 13, 1995)

- "History: Manslaughter, then Justa for All" (B.C. Bookworld, Spring 1995).

Audio recording is the continuation of an interview by Bridget Moran with Ken Rutherford, educator and former municipal politician of Swift Current, Saskatchewan and later ran for the NDP in Fort George, BC. Rutherford discusses his involvement in politics in Saskatchewan, and subsequent move to Prince George, BC and interest in politics in BC.

Audiocassette Summary

- Recalls the 1953 federal election when he ran unsuccessfully as CCF member for Swift Current, Saskatchewan

- After election decided to move to Vancouver; started looking for jobs and took teaching job in Prince George, BC

- Describes living conditions; living in cabin in Fort George and their early neighbors (Milners (sp?) in Prince George c.1950s

- Recalls running in BC elections 3 times unsuccessful

- Discusses MLA Ray Williston and the Wenner-Gren election issue

- Discusses his thoughts on the current NDP; regarding the issue of Senate abolishment and what he sees as ‘undemocratic policies’

Audio recording is of an interview by Bridget Moran with Ken Rutherford, educator and former municipal politician of Swift Current Saskatchewan. Rutherford was an Alderman prior to becoming Mayor of Swift Current from 1944-1952, he ran unsuccessful for the CCF in 1960 and later for the NDP. Rutherford ran for political office in BC in the electoral district of Fort George in 1963 unsuccessfully against Liberal MLA Ray Williston. The interview includes biographical information as well as memories of his career as a school teacher, his political aspirations and involvement with the CCF and later the NDP and the history of medicare in Canada.

Audiocassette Summary

- Rutherford provides genealogical information on grandfather and his mother (her family was from Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan)

- Discusses his parent’s marriage

- Recalls schooling in Swift Current, Saskatchewan where he eventually becomes principal

- Rutherford notes he never went to university, but went to Normal School

- Talks about his wife and children

- Donley Hill

- Recalls joining the CCF and distributing pamphlets; recalls 1935 election and CCF getting few votes

- Recalls salary troubles at the school in Swift Current in the 1930s and being both the teacher and janitor

- He was Mayor of Swift Current from 1944-1952; and previously as Alderman and ran for the CCF in the federal election in 1953;

- Recalls spoiled ballots in the election

- Recalls getting involved with the issue of health premium payments in Swift Current c.1940s.

- Recalls the history of the fight for health care in Canada; and strike in Saskatchewan by doctors

- Recalls the national fight for Medicare – 1961

- Discusses Tommy Douglas; Mackenzie King

- Health care issues

File consists of newspaper clippings:

- "Surrender" (The Georgia Straight, July 19-26)

- "The Kemano deal: scientists, salmon sacrificed" (The Watershed, Nov. 1993)

- "Carrier-Sekani people speak for the fish" (The Watershed, Nov. 1993)

- "Alcan bid rejected by Court"(Canadian Press, Sept. 26, 1994)

- "Kemano hearings concluded" (The Democrat, Autumn, 1994)

- "What's up with Kemano II" (The Democrat, Spring, 1994)

- "How Kemano deal came to happen" (The Prince George Citizen, Aug. 13, 1994)

- "Memos reveal Kemano project conflicts ; editorial comments" (The Prince George Citizen, Oct. 14, 1994)

- "Kemano battle shifts to Ottawa" (The Prince George Citizen, Dec. 9, 1992)

- "Scientists condemn Kemano deal" (The Prince George Citizen, May 27, 1994)

- "North must stick together to protect river" (The Prince George Citizen, Feb. 6, 1993)

- "Controversy clouds start of hearings" (The Prince George Citizen, Nove. 9, 1993)

- "Alcan explains contract" (The Prince George Citizen, July 15, 1994)

- "Fisheries chief stays out of Kemano controversy" (The Prince George Citizen, April 7, 1994)

- "Kemano hearings reconvene in city" (The Prince George Citizen, July 19, 1994)

- "Exemption on Kemano ruled illegal" (The Vancouver Sun, May 25, 1993)

- "Kemano opponents get federal cash" ((The Prince George Citizen, March 31, 1994)

- "Ottawa joins Kemano project inquiry" ((The Prince George Citizen)

- "Your Opinion" ((The Prince George Citizen, Oct. 28, 1993)

- "Kemano hearings almost at an end" (The Prince George Citizen, July 23, 1994)

- "Siddon proud of Kemano deal" (The Prince George Citizen, July 22, 1994)

- "Former fisheries minister testifies" (The Prince George Citizen, July 21, 1994)

- "Social, economic costs of Kemano described here" (The Prince George Citizen, July 20, 1994)

- "Siddon anticipated" (The Prince George Citizen, July 16, 1994)

- Editorial comment on the Kemano project by Carolyn Linden (The Prince George Citizen, July 16, 1994)

- "Pulp mill's effects debated" (The Prince George Citizen, July 13, 1994)

- "Farming issues raised at Kemano hearing" and "Float plane operators worried about project" (The Prince George Citizen, July 12, 1994)

- "Vanderhoof wary about Alcan plan" (The Prince George Citizen, July 11, 1994)

- "Natives seek..." (The Prince George Citizen, June 4, 1994)

- "Where will the power from Kemano..." (The Prince George Citizen, June 11, 1994)

- "Scientists testify at inquiry" (The Prince George Citizen)

- "Threat to Tweedsmuir Park predicted"

- "Protesters disrupt inquiry" (The Prince George Citizen, June 24, 1994)

- "Power struggle" (The Weekend Sun, April 23, 1994)

- "Council rates Nechako 'most endangered river'" and "Alcan finds no evidence of PCB contamination" (Lakes District News, May 18, 1994)

- "Siddon wanted at hearings" (The Prince George Citizen, May 20, 1994)

- "Weed growth fears expressed" (The Prince George Citizen, July 8, 1994)

- "Chemical threat to river feared" (The Prince George Citizen, April 14, 1994)

- Newspaper advertisement: "Five things you should know about Kemano Completion" (The Weekend Sun, April 23, 1994)

- "Retired scientist says he was told to support gov't" (The Prince George Citizen, May 12, 1994)

- "Kemano opponents rifle paper" (The Prince George Citizen)

- "Court rejects Kemano challenge" (The Prince George Citizen, Feb. 4, 1993)

- "Kemano probe called 'a sham'" (The Prince George Citizen, April 14, 1994)

- "Special Kemano 'deals' denied" (The Prince George Citizen, July 15, 1994)

- "Nechako warning 'ignored' in '86" (The Prince George Citizen, May 4, 1994)

- "Scientists say deal bad" (The Prince George Citizen, May 7, 1994)

- "Kemano in jeopardy, gov't hints" (The Prince George Citizen)

- "Kemano inquiry promise sought" (The Prince George Citizen, July 14, 1994)

- "Kemano fight pledged" (The Prince George Citizen)

- "Kemano report 'shocks' natives" (The Prince George Citizen)

- "Single moms worst off"

- "Kemano won't be shut down" (The Prince George Citizen, Jan. 20, 1993)

- "Your Opinion" (The Prince George Citizen, Nov. 25, 1992)

- "Kemano queries keep group busy" (The Prince George Citizen, March 25, 1993)

- "Kemano project battle promised" (The Prince George Citizen, Feb. 5, 1993)

- "Indians get flooding settlement" (The Prince George Citizen, March 17, 1993)

- "A move to damn cabinet action in dam controversy" (Vancouver Sun, Jun 24, 1993)

- "Your Opinion" (The Prince George Citizen, April 7, 1993)

- "Fort Fraser folk just let it all hang out" (The Prince George Citizen, April 10, 1993)

- "Kemano answers demanded" (The Prince George Citizen, April 5, 1993)

- "Nechako 'worth more than a few lousy jobs'" (The Prince George Citizen)

- "Indians gather to reclaim heritage" (The Prince George Citizen, July 7, 1993)

- "Kemano hearings hit the road" (The Prince George Citizen, July 25, 1994)

- "Stand rapped" (The Prince George Citizen, Jan. 26, 1992)

- "Kemano-gov't conflict claimed" (The Prince George Citizen, April 11, 1994)

- "Natives could join inquiry" (The Prince George Citizen, Jan. 24, 1994)

- "Gov't kills Kemano project" (The Prince George Citizen, Jan. 23, 1995)

- "The Kemano decision" (The Prince George Citizen, Jan. 24, 1995)

- "Alcan breaks silence: Kemano decision criticized" and "Long, tiring battle over for Monk" (Prince George This Week, Jan. 29, 1995)

File also includes:

- River Views: Newsletter of the Allied Rivers Commission, vol.1, issue 2 (May. 1992) including Allied Rivers Commission "Policies and Objectives" (July 10, 1991) and "Nechako River winter flow comparison"

- River Views: Newsletter of the Allied Rivers Commission, vol.3, issue 1 (Nov. 1993)

- Blueprint: "Tanizul Timber Ltd. T.F.L 42, updated to 93 / 07

- Brian Gardiner, M.P. Campaign '93 Newsletter

- Gardiner Report - Update by Brian Gardiner, MP re: Fed must act on Kemano.

- Handwritten note by Bridget Moran re: Kemano project.

- Newsletter for the Nechacko Environmental Coalition, Edition 1:14 (Mar/April 1993)

- River Views: Newsletter of the Allied Rivers Commission, vol.2, issue 2 (March 1993)

- Information sheet re: public review of Kemano completion project.

File consists of:

- Press release: "Justa tells a compelling story: B.C. author's fourth book a must read" (Dec. 5, 1994)

- Copy of newspaper clipping: "Fascinating life, times of Justa Monk" (Prince George Citizen, Feb. 2, 1995)

- Copy of newspaper clipping: "Murder led to election as tribal leader" (Vancouver Courier, Dec. 28, 1984)

- Copy of newspaper clipping: "Justa: A Review" (Central Interior NDP News)

- Transcript of "Harkins! Bob Harkins Comment" re: Justa publication (Monarch Broadcasting, Nov. 21, 1994)

- Manuscript: "Teresa" - Bridget Moran (writer)

- "Justa: the life and work of a first nations leader" Chapter Summary

- P.105-120, Interview transcriptions between Bridget Moran and Justa Monk.

- P.121 - 133, Interview transcriptions between Theresa and Bridget Moran (recorded March 25, 1993; transcribed April 9, 1993).

- Interview transcriptions between Bridget Moran and Justa Monk re: ancestors & family

- Interview transcriptions between Bridget Moran and Justa Monk re: life in Portage.

- Interview transcriptions between Bridget Moran and Justa Monk re: working before trouble

- Interview transcriptions between Bridget Moran and Justa Monk re: before road (tape 6)

- Interview transcriptions between Bridget Moran and Justa Monk re: Lejac

- Handwritten notes

- Handwritten transcript of interview with Adelle (Oct. 6, 1993)

- Annotated drafts of Chapter 21

- Handwritten notes

- Copies of newspaper clippings re: Justa Monk's trial: "Accused weeps during testimony"; "Murder trial held in Supreme Court"; "Drinking preceded death"; "Stabbing victim: always fighting"; "Defence delivered in murder trial"; "Justa Monk given two years in jail"

- Handwritten notes.

File consists of annotated transcript of interviews between Bridget Moran and Justa Monk.

File consists of:

- "Past mistakes recorded in new book" (Vancouver Sun, May 8, 1995)

- "Murder led to election as tribal leader: social worker recorded story" (Vancouver Courier, Dec. 28, 1984)

- Transcript of "Harkins! Bob Harkins Comment" re: Justa publication (Monarch Broadcasting, Nov. 21, 1994)

- "Fascinating life, times of Justa Monk" (The Prince George Citizen, Feb. 2, 1995)

- "Justa: A Review" (Central Interior NDP News)

- "Blanket coverage" (B.C. Bookworld, spring 1995)

- "Manslaughter, then Justa for all" and "Blanket coverage" (B.C. Bookworld, spring 1995)

- Fax from Laura Boyd, Northwood Pulp & Timber to Justa Monk (and Bridget Moran?) re: names and positions of executive staff at Northwood (Nov. 14, 1994).

Photograph depicts Justa Monk standing to right of Premier Harcourt in unknown room. John Alexis can be seen between them in background. Handwritten annotation on recto of photograph: "Justa Monk / John Alexis Tachie Village / The Premier / Taken in Prince George, B.C. Jan 23/95 / 'The day Kemano 2 was killed'."

Photograph depicts Justa Monk standing to right of Premier Harcourt in unknown room. John Alexis can be seen between them in background.

File consists of a videocassette (VHS) recording of Justa Monk giving a talk to a UNBC Carrier Culture Course (First Nations Studies 163) on October 24, 1995.

Videocassette Summary

Context: Justa Monk speaks to students in the UNBC Carrier Culture Course (First Nations Studies 163)

Introduction: Justa Monk is seated at a table situated at the front of a lecture theatre (?) speaking in a lecture style that ended in a question-answer format with several students in the FNS 163 class. The videotaping does not commence from the beginning of the lecture as there is no introduction to Justa Monk by the instructor and there is no immediate indication as to who the instructor is.